Travels with Julia || Nicaragua

Maybe because growing up in a family that endured the last world war in Italy, often hungry, my journey as a writer is concerned with food. For me, everything about it fascinates—growing it, harvesting it, cooking it, understanding its cultural trajectory. The recipes are metaphors, albeit edible ones.

When I traveled to Nicaragua recently to meet up with my daughter and make our way together to a remote village in the country’s highlands, I learned such a recipe, one that has come to have meaning for me far beyond the discovery of a new dish. It was a sweet corn cookie, called rosquillas, that left a lasting taste of more than the sum of its ingredients. These ancient cookies are pervaded not only with the inimitable flavor of nixtamalized corn that I have come to crave. They come with them a powerful back story of guts, grit, and grace.

Gabriella took me to El Largartillo to live among the villagers and study Spanish at Hijos del Maiz Campesino Spanish School, “Children of Corn Peasant-Farmer Language School,” an unusual project conceived to teach Spanish and share the campesino way of life with outsiders. In my short time there, I became immersed in the spirit of this special place, and learned of its tumultuous history.

In my story, I wrote:

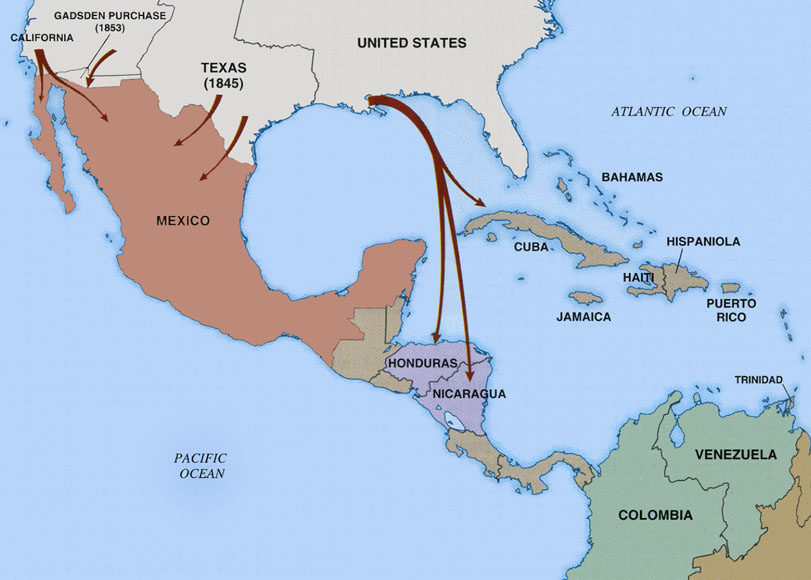

For five centuries, many foreigners have been lured by this sizzling land of volcanos and cloud forests. From the conquistadores to William Walker, the American military adventurer who installed himself as president in 1856, to the U.S. Marines in the early 20th century, Nicaragua has endured conquest, occupation, oppression and brutality.

Concepción, one of two active volcanoes that form the northwest part of Isla de Ometepe, Ometepe Island, on Lake Nicaragua. | Photo: Celina della Croce

Map of invasions led by the American military adventurers, William Walker, who ravaged Latin American countries with paid mercenaries.

Fast forward to the victory of the Sandinistas over the American-backed Somoza regime in 1979. The village I visited, situated on land once controlled by the dictator, was founded by twenty-six campesino families whose members were part of the peasant uprising against him. They banded together after the insurrection and made their way to this remote site with a vision to build a self-reliant farming cooperative modeled after some of the successful agrarian projects of other non-competitive economies, like Cuba’s.

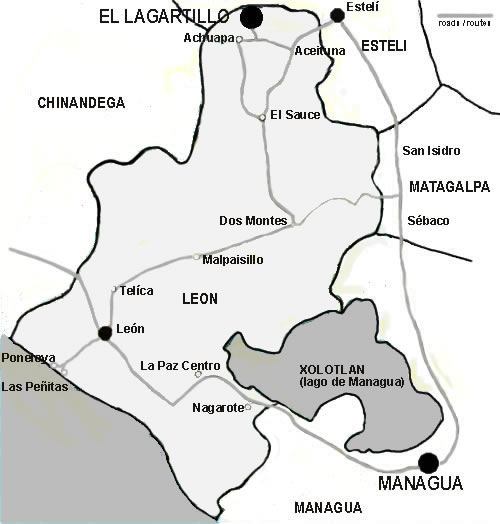

Detailed map of Nicaragua; El Lagartillo in the north eastern mountains. | Photo: Hijos del Maiz Campesino Spanish School

It took the villagers two years to build their houses. In the meantime, they lived together like one big family in a single-room school they put up first. The Sandinistas had already made progress in providing public health, education, and eliminating illiteracy. Tina Pérez describes the country’s hopes after the revolution: “The Literacy Crusade lifted us out of the darkness in which we were submerged….One of our precious dreams came true—to learn to read and write” (from La Vida di Tina, London, 1994). They worked their hard-won land, even while Oliver North and his counterrevolutionaries were “busy blowing up Nicaragua” [sic] (Landslide: The Unmaking of the President, 1984-1988) to overthrow the new government in Ronald Reagan’s secret war.

In 1984, less than two months after the farmers completed their houses and planted their fields, the village was ambushed by CIA-financed and organized contras. It was U.S. strategy to target agricultural peoples, the object to disrupt food production and terrorize the population. The attack came early on New Year’s Eve, 1984, while most of the self-defense team was busy in the outlying fields. An estimated 100 to 150 contras surprised them, bearing U.S.-issued rifles and mortars. They encircled seven terrified campesinos, including 20-year old polio-stricken Maria Zunilda (Tina Pérez’s daughter); her father, Angel (Tina’s husband); two fourteen-year old boys (one, Francisca’s son), and Javier Perez (Tina’s nephew), and shot them before incinerating the village. “We are Reagan’s freedom fighters,” one young contra was reported to have announced in another, nearby attack. (Nicaragua: Surviving the Legacy of U.S. Policy, Photography: Paul Dix | Editor: Pamela Fitzpatrick).

Many of the survivors described how they fled with their children, leaping off treacherous drops on the mountainside to escape (every New Year’s Day at dawn, they walk the same path to re-enact the flight). Two small children, one, now my language teacher, Lisbet, and her polo-stricken cousin, Juan, were hidden, huddled together in an underground concrete trench the campesinos had dug as a shelter in the event of a hostile raid. Lisbet recalled that the contras had paused in front of the camouflaged opening in the ground with the intention of stuffing it with an explosive device, but became distracted. Juan, today the village librarian, remembered the incident vividly.

The story of Tina Pérez Calderon was publicized by the actor Richard Gere, and told many times when a Witness for Peace congregation brought her to the United States in 1986 as part of an effort to stop the war (follow the links to Witness for Peace site to learn more). Many people did not believe her story. They perceived Americans as liberators, as did Ronald Reagan himself.

The same year, she returned to the site with other survivors. They obstinately rebuilt, considering it sacred ground. A new school and fifteen houses went up, and water was brought to the village. As the war moved to other parts of the country, the men went back to the fields to farm in a traditional way that honored the land. The villagers are determined to keep alive the memory of the war. Signs, monuments, remembrances and photographs of the slain are everywhere, in houses and public places.

I was astonished that the people of El Lagartillo found it in their hearts to forgive the contras and their U.S. backers. Having studied political science and lived through this period of American history, I still could not find an answer to a question someone asked me about how it could be that most people in America knew very little about what their own country had done. I could only feel humbled, and bear witness to the tragic truth of that. Most remarkable of all to me was that they invited us into their homes as they would one of their own, fed us, shared their memories, and wore their pain. I know for sure that my heart will never be the same.

As the sun began to set on the evening before we bade our farewell, I saw the El Lagartillo experiment as it really was. Men helped one another unload supplies from the sole pickup owned by the village. Amparo’s brother was in the backyard, dismounting from his horse with a sack of corn from the fields with which his sister would make tortillas for three families. She cooked and gossiped in the kitchen with Maribel, a neighbor. A small boy holding Maribel’s hand was shouting at his mother. The two women scolded him for his bad behavior. A campesino carrying a whip was passing by in front of the house, herding his cattle as they stampeded past, bellowing to their calves that awaited them behind a corral at the edge of the forest.

Nearby, where Gabriella stayed, we found her host Francisca behind the house, firing up a large cob oven built on a boulder in the dirt. Other women from the village flocked around her to help. The wood-fueled oven can bake 600 rosquillas before the embers die out, enough for each helper to keep a batch for herself, enough to give some to us for our journey back to León the following day.

Back at Amparo’s house, we settled down into rocking chairs, gazing through the front windows and chatting as had become our habit before bedtime. Tonight, munching on the rosquillas with her, I realized that I had been accepted into the village. Whether Francisca meant to bake the cookies as a way of saying goodbye or not, I’ll never know, but they came to symbolize, for me, the grace and generosity of this very special place. I have called them magical cookies because they conjure up the memory of El Lagartillo, and how it transformed me. I am far away from the village and the people, but they are with me, often. When I make the rosquillas, I feel their spirit.

Follow

Follow

email

email

Thank you, Julia for this very touching piece.

That was an amazing story. Thanks for sending it.

It was that, GG, despite some academic background in Latin American relations. I was reading about the history of our foreign policy in Nicaragua—the books I mentioned in my article—while I was sitting in Amparo’s rocking chair every morning and witnessing the truth of these accounts in situ. I only wish all school children were taught an objective view of American militarism in our history. We might produce fewer proponents and apologists for such unprovoked aggression against helpless countries. As citizens, we are quite unaware of the true motivations and consequences of much of our policy.

Fine, interesting and moving account.

I feel privileged to have been invited into this very special place, to have been able to share their very moving story. As Americans, it’s only too easy to be blinded to the implications our foreign policy abroad and how it affects other human beings. I hope to have been able to make a small contribution to an understanding of what happened in this beautiful country. Thank you for your comment.

I would like to say that this post is amazing.

I am Florentina’s eldest granddaughter and every now and again I check online, to see if any visitors of El Lagartillo have posted anything about her or her story.

Yours is probably my favourite! I especially love the photo of her with the cuajada!

Thank you so much.

Your comment brought back a flood of memories of your mother and the remarkable survivors of El Lagartillo a year and a half ago and I just wept. Your message means a great deal to me. Thank you so much for sending it, Angelica. I don’t know if you saw it, but I published a secondary article on Zester Daily soon after about that magical cookies. Here is the link: http://zesterdaily.com/cooking/corn-masa-cookies-in-nicaragua/. Here’s to all the blessings of the universe on you and your family and El Lagartillo.

Beautiful post, please send us some of the cookies! 😉

https://youtu.be/jVmmGlRjpOA

Thank you. Would you like the recipe for the cookies?