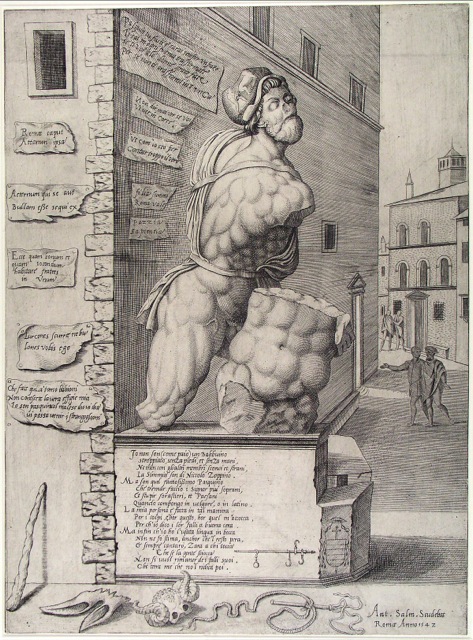

Just when I was thinking I should offer a recipe with an accompanying historical yarn about abbacchio, the suckling lamb that is Rome’s gastronomical obsession at Easter, this lively story about just that, titled “Pasquino Discusses a Tender Subject” landed in my mailbox. The author, Anthony Di Renzo, who chronicles a fading Italian world in his novels, writes a column for the California-based L’Italo-Americano newspaper under the pen name, “Pasquino.” For those not steeped in Roman lore, “Pasquino” is the nickname of an ancient, battered statue that lost its arms during the sack of Rome and was buried in a ditch until April Fool’s Day, 1501.

After the ruin was dug up and heaved onto a pedestal, it became a soapbox for anticlerical squibs (from which derives the English word “pasquinade,” or lampoon) and local sarcasm (at which the Romans excel). Pasquino still observes the goings on of the city, large and small, his opinions voiced in the placards and graffiti displayed around his remains. Here in America, Anthony’s column channels the statue’s ruminations. In time for spring holiday celebrations, the marble hulk muses on abbacchio, as imagined by him. You will learn the history of the iconic dish—”Not bad for a hunk of stone,” Anthony says— and from me, the recipe (below). Buona Pasqua a tutti, and Happy Spring Equinox to all!

A mile and a half from the Circus Maximus, sheep graze in Caffarella Park. Warming themselves in the April sun, they are indifferent to the ruins of towers and mausoleums and oblivious to an annual rite of spring. Shepherds gather and transport the youngest of the flock for slaughter and sale at Piazza San Cosimato and Piazza Testaccio. As Easter approaches, Rome once again craves abbacchio, suckling lamb.

Pasquino protesting city plans to privatize water, 2012. | Credit: La Repubblica Roma

Abbacchio was a delicacy before the city’s founding. When Italic shepherds roamed free, sheep were Latium’s basic monetary unit, called a pecus. Their skin and wool provided clothing. Their milk, cheese, and meat supplied protein. When Roman law was codified, peculium (the Latin root for “pecuniary”) came to mean transferable property, sometimes in the form of pasturage or livestock. The Divino Amore district, between the Alban Hills and central Rome, was the best range in classical times. The best abbacchio, connoisseurs swear, still comes from here.

According to Juvenal, who satirized Rome’s imperial appetites, true suckling lamb should be “more milk than blood,” killed before it tastes its first grass. The tender-hearted may weep, but the tough-minded shrug. Lambs are not harmless. They nibble everything in sight and compact and erode the soil. Dairy ewes live about a decade, producing up to four lambs a year. When too many threaten to deplete a pasture, ranchers whisk them to the slaughterhouse, the sooner the better.

The term abbacchio reflects this cruel reality. Abbacchiare means to beat down or demoralize. The verb derives from bacchiare, to beat fruit from trees with a bacchio, a long stick called a baculum by the ancients. Suckling lambs were carried to the Forum Boarium with their hooves twined over the baculum and were slaughtered with it. Abbachiare also means to sell at bargain-basement prices, to dump on the market, because the overabundance of spring lambs always drives down prices. During the early Christian era, however, butchers jacked prices and gouged customers. Everyone was expected to eat abbacchio at Easter, so demand always exceeded supply.

The “agnellatura,” lamb slaughter. Woodcut. Artist unknown. | Courtesy: La cucina romana e del Lazio, Livio Jannattoni (Newton & Compton Editori, 1988)

The Lamb of God proved good business. Even the shepherds of the church profited. Medieval popes abandoned to pasture huge tracts of land extending from the gates of Rome to the borders of Tuscany and Umbria. To fund protection against local authorities and to replenish its treasury, the Vatican established a dogana dei pastorizie. It taxed all flocks within its purview and collected rent on all pasturage.

Stuff or spice baby lamb with minced rosemary and garlic and roast it with new potatoes. That’s abbacchio al forno con le patate, the centerpiece at Easter dinner. Braise the lamb in broth with white wine and scrambled egg yolks and slurp abbacchio brodettato, an Easter Monday specialty. Cleave it into dainty chops, sprinkle them with rosemary, and grill them for abbacchio scottadito, so named because the chops burn your fingertips. If you sauté the lamb’s internal organs instead, adding slivers of artichoke hearts, you get coratella con carciofi. This hearty dish tastes best on Easter morning around ten, whether or not you’ve fasted on Holy Saturday. Tough luck makes tender flesh. Despite its unsavory history, abbacchio is too succulent to resist. Unlike grass-fed lamb, suckling lamb is pale, buttery soft, and sweet. Slaughtered at one or two months old and weighing between 15 to 20 pounds, abbacchio has burned off most of its baby fat but has not developed muscle. Every ounce of the animal is consumed with relish, from legs to ribs, organ meats to intestines. At a trattoria near Campo de’ Fiori, a waiter recites a litany of mouthwatering recipes to Maryknoll nuns on pilgrimage.

The Mother Superior, raised on a Nebraskan sheep farm, orders pajata d’abbacchio: lamb chitterlings stewed in tomatoes and served with rigatoni. A baby-faced novice wonders whether it is right to eat lamb before Easter but swallows her scruples with the first bite. That’s human nature. We beat our breasts and lick our fingers.

The author, Anthony Di Renzo, a fugitive from advertising, teaches writing at Ithaca College. His essays and stories satirize the ongoing culture war between Italian humanism and American business and technology. (Italy usually loses.) He lives in Ithaca, New York, an Old World man in a New Age town.

More on Cooking Lamb the Italian Way

Historically and until the present day, enormous quantities of abbacchio have been consumed in Rome from Easter until summer (for example, in 1629, the city alone recorded selling 165 thousand for 115 thousand inhabitants). A look at any Roman menu, or any Roman cookbook, for that matter, will show that meat is preferred to any other food, even bread. Thus it is not surprising that Romans are very discriminating in all matters of meat. They like it very young, preferring suckling pig, suckling goat, and suckling lamb to grass-fed animals. Milk-fed lamb has none of the gaminess of older lamb and tastes, as Anthony describes, buttery and sweet. Abbacchio is raised for slaughter between autumn and spring, its season ending on the feast of San Giovanni, June 24.

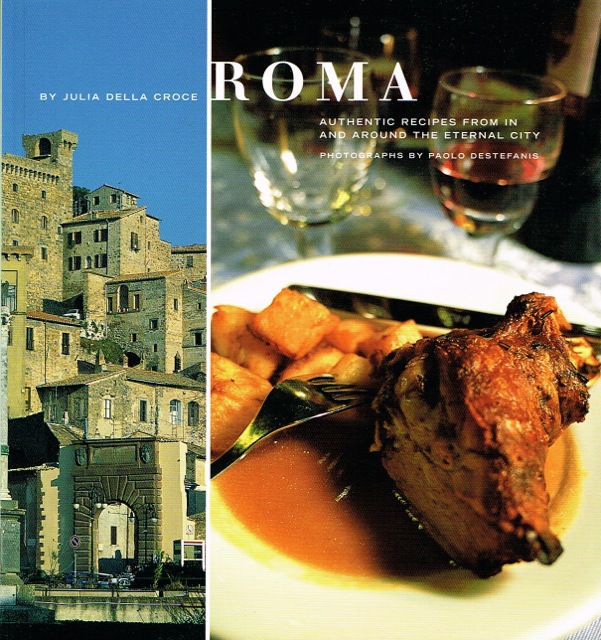

Roman abbacchio with potatoes is the Easter centerpiece at home or in restaurants. | Photo: Paolo Destefanis

Other southern regions, particularly Sardinia, are satisfied with older animals as well, and eat it all in prodigious amounts, applying countless delectable local ways of preparing it nose-to-tail.

Milk-fed and older lamb and goat at market in Catania. | Photo: Paolo Destefanis

Neither the Americans nor the English typically slaughter lamb at such a tender age, but a good butcher can tell you when to order a baby animal in time for the holiday. If you can still get one at this late date, here is a recipe for abbacchio. If not, my recipe for roasted leg of lamb also follows. A general note about lamb: In the interest of flavor and health, it is best to procure organic, truly “all-natural,” or traceable locally raised meat (rather than industrially farmed). Niman Ranch is one such lamb producer that distributes its meat in markets nationwide.

Abbacchio, photo, right, by Paolo Destefanis for Roma, by Julia della Croce (Chronicle Books)

Roast Milk-Fed Baby Lamb

abbacchio al forno

For 8 people

From Roma: Authentic Recipes from In and Around the Eternal City, by Julia della Croce (Chronicle Books, 2004)

The famous Roman abbacchio, milk-fed baby lamb not older than six weeks, goes down your throat like butter when it’s cooked. The best way to prepare this delicious meat is to do as little as possible to interfere with its natural flavor. The lamb needs no marinating, and no sauce save the pan juices. Have a butcher prepare the lamb for roasting. Be sure he cracks the joints so you can arrange the lamb on the rack on a roasting pan. Enough fat should remain on the meat to keep it moist while it cooks.

1/2 milk-fed baby lamb (15 to 20 pounds)

4 large cloves garlic, cut into slivers

1/4 cup extra-virgin olive oil

2 tablespoons minced fresh rosemary, or 1 tablespoon dried rosemary

freshly ground black pepper to taste

Remove the lamb from the refrigerator 1 hour before roasting. Preheat the oven to 400º F. With a small, sharp knife, make numerous small incisions on both sides of the lamb: in between the ribs, on the shoulder and leg, and between the joints. Slip garlic slivers into the cuts. Rub in the olive oil, rosemary, and pepper. Tie the legs together with kitchen string. Place the meat on a rack in a large roasting pan. Slide the pan onto the middle rack of the oven. Immediately lower the heat to 350º F. For “pink” lamb, roast 12 minutes per pound. After 30 minutes, remove the lamb from the oven and close the oven door (to keep the oven temperature constant). Baste the lamb with its own juices and return it to the oven. Repeat every 20 minutes.

Remove the lamb from the oven when the internal temperature of the thickest part of the meat reaches 130 degree F, and the surface is nicely browned, sprinkle with salt, and tent loosely with aluminum foil. Let rest for 15 to 20 minutes. Carve the meat and serve on a warmed platter with the degreased pan juices.

Roast Leg of Lamb My Mother’s Way

Agnello alla sarda

For 8 people

From The Classic Italian Cookbook, by Julia della Croce (DK Publishing, 1996)

Nothing reminds me more of my childhood, and of Sardinian cuisine, than lamb roasted over the embers of a hardwood fire. The method is simple, and the results, utterly delicious. An indoor wood-burning oven is not a feature of the average modern kitchen, but an outdoor coal-burning grill can be substituted. It is important, however, to start the fire with kindling rather than chemical fire-starter, which affects the flavor and aroma of the meat.

1 leg of lamb, trimmed (about 6 pounds)

For the rub:

3 large garlic cloves, minced

2 teaspoons minced fresh rosemary, or 1/2 teaspoon dried crushed rosemary leaves

1/3 cup minced fresh Italian parsley

1/3 cup extra-virgin olive oil

1/2 teaspoon freshly milled black pepper, coarsely ground

fine sea salt

Bring the lamb to room temperature. Combine the ingredients for the rub. With a small, sharp knife, make shallow, evenly spaced incisions on all sides of the leg. Work the rub into the incisions. With your hands, work the remaining rub into the surface flesh of the lamb. Transfer the lamb to a roasting pan and allow it to stand at room temperature for 2 hours.

For an outdoor grill:

Use dry hardwood such as oak, if possible. Alternatively, use charcoal. The grill is ready when the embers or coals are at their hottest, that is, white and glowing. Arrange them around the edges of the grill to produce indirect heat, leaving a few coals in the center. Transfer the lamb to the grill; cover the grill, turning occasionally, until the internal temperature of the thickest part of the leg registers 130 degrees F for medium rare, 45 to 60 minutes.

For oven-roasting:

If roasting in an oven, adjust the oven rack to the middle position and preheat to 400 degrees F. Reduce oven temperature to 350 degrees and roast lamb until the internal temperature of the thickest part of the leg reaches 130 degrees F, about 1 hour.

Transfer the lamb to a serving platter; let stand for 10 minutes. Sprinkle it with sea salt to taste. Carve and serve immediately with defatted pan juices.

Julia della Croce is a New York-based author and journalist who writes about the culture of food and drink. Her thirteen books chronicle the vanishing Italian cooking of her childhood.

Fork illustration: Winslow Pinney Pels

With gratitude to Anthony Di Renzo

Follow

Follow

email

email

Great post Julia…love the Pasquino statue! We are going to have to just bite the bullet when we are in Rome and have the lamb. My husband, I am sure will order the Pajata! After all it is a delicacy…politically incorrect, not too sure…the Romans don’t seem to think so and as they say “when in Rome”…

Pagliata is Rome’s ancient answer to chittlins. It’s delicious. I grew up on this and other so-called variety meats because my mother spent ten years in Rome as a young woman and gathered her cooking skills there. I guess you have to have a palate for it—most Americans didn’t grow up eating it. But it is delicious. Buon viaggio!